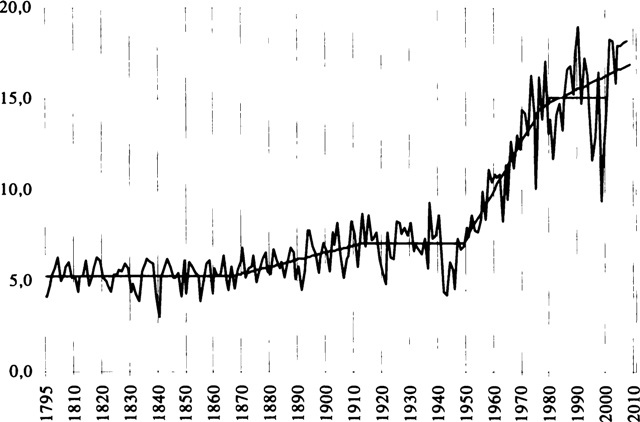

Bread yield in Russia over 200 years

Grain yields in the USSR, compared to the Russian Empire, rose from 6-7 c/ha at the end of its existence to 15 c/ha at the end of Soviet power. That is, two to two and a half times. The main rise occurred during the reign of Khrushchev and Brezhnev - due to the chemicalization of agriculture and the use of new varieties of grain. (In the Russian Empire, it was not wheat, which was more capricious to climatic conditions, from which white bread was produced, but rye, from which black bread was obtained; white bread was “for the gentlemen”; the introduction of white bread into people’s everyday life - so that it was almost replaced black bread - this is a merit of the conscientious authorities; however, there are also disadvantages: rye would produce more abundant harvests in Russian conditions and is less demanding of climatic conditions). And at the same time, the USSR, let us remind you, also imported about 20 million tons of grain per year! And the USSR did not have enough grain to develop its own livestock farming - that is, primarily for meat production. The increase in yields during Putin's reign is apparently the result of favorable climatic conditions: after all, the use of chemical fertilizers has decreased, the area under cultivation has decreased, the provision of rural areas with agricultural machinery has deteriorated - why then would the yields increase? So for now Putin is lucky with the weather. It is also clear that dispossession (that is, the elimination of “strong owners”) and collectivization, as well as mass slaughter of livestock (which led to a decrease in the amount of organic fertilizers received) on average had almost no effect on grain yields - that is, on the efficiency of management. It should also be taken into account that the increase in yield was “eaten up” by the increase in population - so that on average per capita the increase in grain production in Russia was not so significant; however, the increase in grain production still offset population growth.

So explain: how did the Russian Empire feed so many people all over the world by exporting bread, and why on earth under Putin did Russia begin to export grain again, if the USSR at the end of its existence imported 20 million tons of grain and there was still not enough for the development of livestock farming? ! The answer is simple: “we don’t have enough to eat, but we’ll take it out.” This principle, apparently, was adhered to by St. Nicholas II and his predecessors on the throne.

Original taken from polit_ec in Crop yields in Russia over 200 years

Who knows how many centners per hectare is the yield of “one-six”? What progress did Russian peasants achieve after the abolition of serfdom and what progress did Stalin’s collective farmers achieve? The most interesting data on grain yields in our country for the period from 1795 to 2007 were published in the academic monograph: Rastyannikov V.G., Deryugina I.V. Bread yield in Russia. M., 2009. This is not the first work by well-known specialists on the problems of the history of agricultural statistics. It collects and analyzes a huge amount of information, which allows us to trace trends in such an important indicator as grain yield over more than two centuries of Russian history.

For historical comparisons, it is essential to use comparable data. Meanwhile, the methodology of agricultural statistics in our country has changed several times.

It is known that tsarist statistics significantly underestimated real production volumes. This was due to both accounting problems and the reluctance of the peasants to reveal to the “bosses” the true situation of their farms. On the contrary, Soviet-era statistics are known for large-scale additions - not only to individual leaders who wanted to report on the successful implementation of the plan, but also at the state level to prove the advantages of socialism.

For example, during the Stalin years, the standing crop was taken into account, which “represents the entire harvest in the field, down to the last grain. This is the harvest that could be harvested if there were absolutely no loss or theft of grain during harvesting and threshing.” During Khrushchev's time, they switched to recording the barn harvest - actually collected and entered into storage. But since 1966, the category “collection” was introduced instead, which again led to “creeping falsification” of statistics. In the last pre-Gorbachev years, in conditions of growing food difficulties, data on grain harvests and yields completely disappeared from the pages of the statistical yearbooks of the Central Statistical Office of the USSR. The ban on their publication was lifted only in 1985.

What does this discrepancy lead to? Quite often you can see how one author cites data from pre-revolutionary publications; another from archival documents from the 1930s; the third operates with late Soviet statistical collections; and no one suspects how different the methods of calculation used in these sources are. It is clear that there can be no talk of any intelligible comparison. Therefore, the monograph under consideration, where information about yields is, as they say, “reduced to a common denominator,” is of great interest.

Naturally, I cannot ignore my favorite topic - a comparison of the Russian Empire and the Stalinist USSR. The book analyzes the dynamics of yields in different historical eras.

From the end of the 18th century until the abolition of serfdom, the average grain yield in Russia did not increase. From the 1860s until the revolution, there was a steady increase in yields, and towards the end of the period it was increasing. The most fruitful years of the Russian Empire were the legendary 1913 and... the war year 1915.

With the establishment of Soviet power, yield growth again stopped for more than three decades. There was an old joke: how to decipher the name of the party VKP(b)? Answer: Second serfdom (Bolsheviks). Judging by the dynamics of grain yields, there is a large grain of truth in this joke. Soviet power, like serfdom, led to stagnation in crop yields.

Only from the mid-1950s did yields begin to steadily exceed those of pre-revolutionary Russia. If before this the 1913 level was surpassed exactly once, in the fabulously productive year of 1937, then the next time this happened in 1956, and after 1964, Soviet harvests never fell below the 1913 level. Chemicalization has finally reached Russia. But, as in other areas of life, Soviet power led to the loss of more than 30 years for the development of our country.

Since 1979, a new period of stagnation began, which lasted until the end of the 1990s. During the same period, difficulties grew in the economy, in food supplies, in ensuring the standard of living of people, which ultimately led the Soviet Union to collapse. And only since 2000, along with the general rise of the Russian economy, harvest growth has resumed.

This is the history of Russia in miniature that the yield curve paints for us. If you think about it, the coincidence of development trends in agriculture and the whole society is not at all surprising.

For comparison: USDA wheat yield data for 1914

():

US Department of Agriculture (USDA) data on grain yields in 2014 in individual countries and on average in the world.

These figures were published in mid-August 2014. The variation in the level of productivity of wheat cultivation in different countries is based on the natural climatic factor, the conditions for the production of grain wheat, as well as the general technological level of cultivation of soils and crops in different regions.

The highest wheat yields are traditionally noted in Europe: in Germany - 7.95 t/ha; in Great Britain - 7.8 t/ha; in France - 7.3 t/ha. Among the European outsiders are Bulgaria and Romania with wheat yields of 4.18 and 3.57 t/ha, respectively.

Among Asian countries, China stands out in terms of yield, where they harvest more per hectare than the world average - 5.23 t/ha. On the other side of the Himalayan range, in India, wheat yields are much lower - 3.13 t/ha. In the arid countries of the Middle East, wheat yields are even lower: in Turkey 1.95 t/ha, in Iran - 1.91 t/ha.

In the US and Canada, wheat yields are almost the same. In 2014/15 agricultural In 2018, wheat yield in the USA is predicted to be 2.95 t/ha, in Canada - 3.01 t/ha.

In Argentina, the yield of grain wheat is comparable - 2.98 t/ha. Compared to these countries, the yield in Australia is relatively low: in 2013 - 2 t/ha, in 2014 - according to the forecast, 1.88 t/ha.

Among the three major grain-producing Eurasian countries, the highest wheat yield was recorded in Ukraine - 3.49 t/ha. In Russia, the yield is 2.48 t/ha. In Uzbekistan, wheat yields are high thanks to irrigated agriculture - 4.86 t/ha. And Kazakhstan closes this group of countries. According to the expert group, wheat yield in Kazakhstan is more than 3 times lower than the world average, namely 1.06 t/ha. At the same time, the world average yield of this grain in the world was 3.22 t/ha

__

That is, in Germany the wheat yield is 79 c/ha, and in Great Britain - 78 c/ha.

But how Russia managed to get 24 c/ha is not clear; However, 15 c/ha at the end of the USSR is, apparently, the average yield of all grains in general, and not just wheat.

Here is a sign from Wikipedia about wheat production

(https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/%D0%9F%D1%88%D0%B5%D0%BD%D0%B8%D1%86%D0%B0#.D0.A3.D1.80 .D0.BE.D0.B6.D0.B0.D0.B9.D0.BD.D0.BE.D1.81.D1.82.D1.8C_.D0.BF.D0.BE_.D1.81.D1 .82.D1.80.D0.B0.D0.BD.D0.B0.D0.BC):

A country |

|---|